11

FUELS & LUBES INTERNATIONAL

Quarter Two 2015

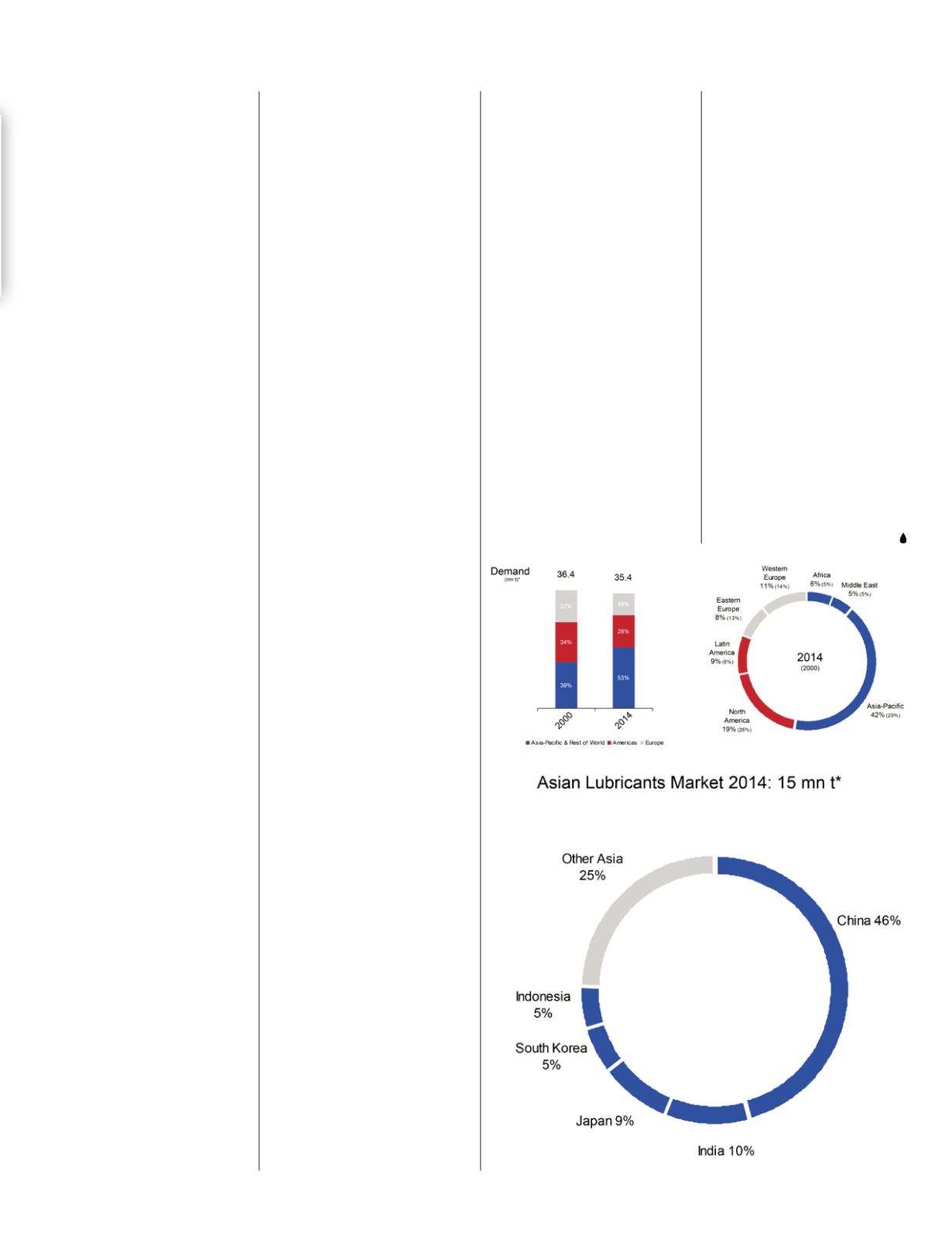

U.S. economy started to recover in

2014. “The markets in Asia-Pacific

are not only emerging markets,”

Gosalia said, “they are also mature

markets. Growth rates in India and

China are still there, but on a much

lower level than it used to be before,

and markets like Japan and Korea

actually declined in 2014.”

In 2014 there was a noteworthy

contrast between global lubricant

demand and per capita lubricant

demand. Globally, China had the

largest demand for lubricants,

but as a country among the top

20 lube-consuming nations, it

has the second lowest lubricant

demand per capita, less than

the world average, which is 5

kilograms (kg) per year. The same

is true for Asia-Pacific as a region.

This only means one thing: a

higher upside potential for Asia-

Pacific.

“This speaks to the volume

potential that China has,” said

Gosalia. “China is a market

in transition, on the edge of

becoming more and more a

mature market.”

In terms of China, there

are two forces working against

each other, he said. “What

happened in Europe and North

America over a period of 20

or 30 years is happening much

quicker in China because

on the one side, you’ve got

increasing motorisation and

industrialisation, so people who

were riding a bike may switch and

buy a car.” On the other hand,

“people don’t just want to buy a

car; they want to buy the best car”

in China, and those require high-

quality lubricants.

This contrasts with the

North American market, which

consumes the highest amount

of lubricant per capita by far:

nearly 20 kg per year, double

that of the average Western

European. However, “they [North

Americans] still have a long way

to go in terms of quality,” because

there is a higher tendency in

North America to buy a cheap car

or to use a low-quality lubricant.

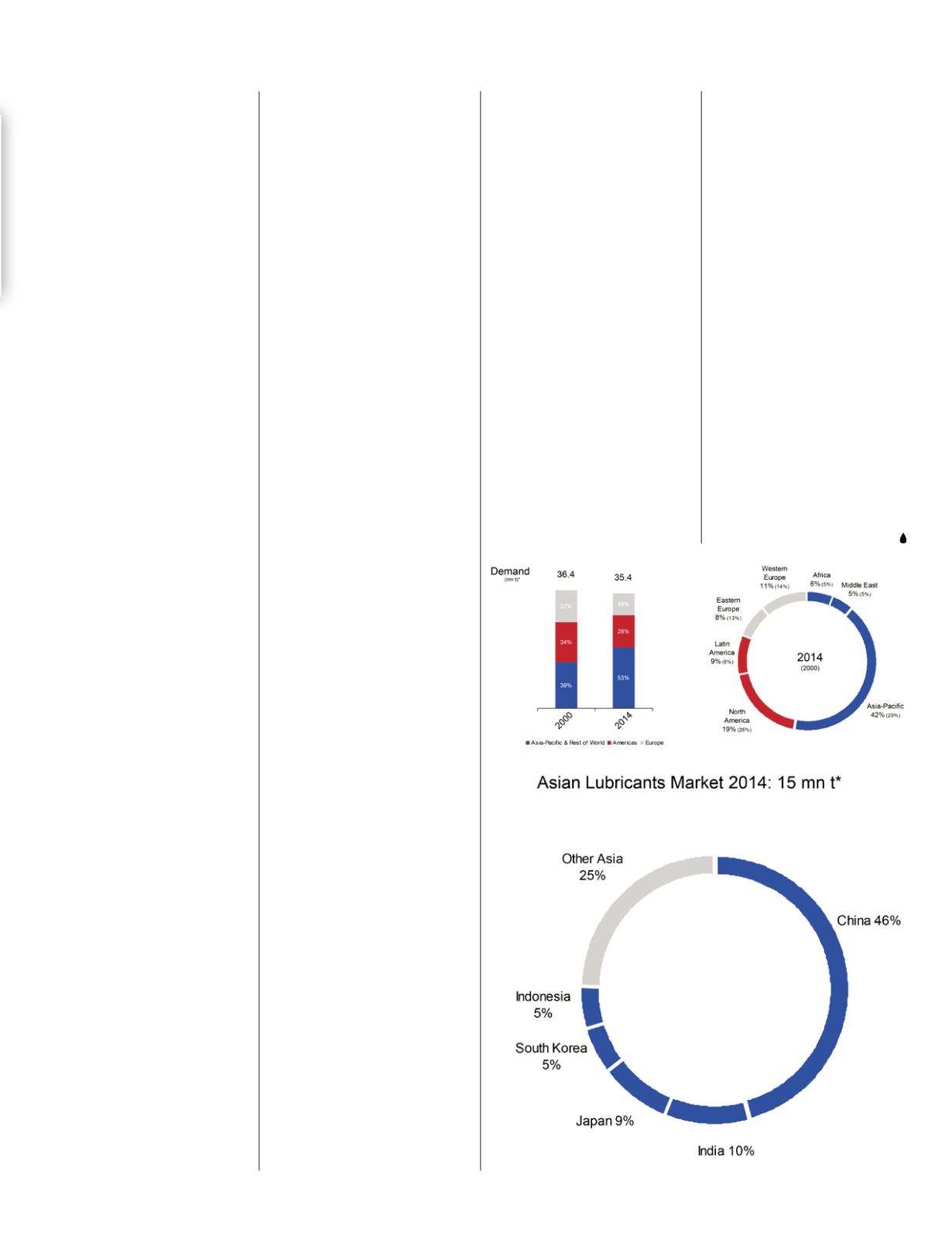

Gosalia introduced data on

lubricant demand in China,

India, Japan, South Korea

and Indonesia to explore how

lubricant demand correlates

with other factors, such as steel

production, car production,

mineral oil demand and gross

domestic product (GDP) in

each country. Gosalia showed

data from 2007 to 2014, and in

each case, GDP and lubricant

demand grew apart from each

other, with lubricant demand

decreasing. As consumers have

more money in their pockets,

he explained, they tend to buy

higher quality products, which

means longer-drain intervals and

which translates to lower volume

demand growth.

Most people know that

the industry is increasingly

competitive, and Gosalia

presented data illustrating one

reason for this. Between the

mid-1990s and 2005, according

to a joint study by Fuchs and

the University of Mannheim

in Germany, the number of

independent lubricant companies

decreased from 1,500 to 590. The

number of “majors” decreased from

200 in the mid-90s to 130 in 2005.

(This study only included players

producing 1,000 tonnes or more.)

“This speaks to the

fragmentation of the industry,”

Gosalia said. “At the end of

2005, the top 10 manufacturers

made up 50% of the global lube

market, leaving the other 700

manufacturers to share the rest.”

This data came from a very

extensive study, which may be

repeated in a year or two, but for

now, the latest available data is

from 2005.

Factors causing industry

contraction include the

globalisation of national

oil companies, new market

participants, vertical

diversification, the role of private

equity, restructuring of majors

and retraction from niches. In the

past two or three years, Gosalia

said, there have been several

examples of large oil companies

that have “retracted from niches of

the lubes industry and left the field

open for other, more specialised,

focused lube companies… to buy

these businesses.”

Between 2000 and 2014,

the list of the top 15 lubricant

manufacturers was shuffled around

as a result of these phenomena.

Between 2000 and 2014, three

new players appeared on the list:

Petronas, Gulf/Houghton and

Pertamina. Other companies,

including Indian Oil Corp., AGIP

and Repsol, left the top 15.

In light of all this

restructuring, the word

“sustainability” takes on a

different meaning.

“These days, everything’s

sustainable,” Gosalia said.

The word has lost some of

its significance as so many

companies try to improve their

public image by “greenwashing.”

A much more real concern for

most companies is, literally,

sustainability—surviving in a

competitive and contracting

marketplace. Fuchs had to define

sustainability for itself so that it

could be measured, said Gosalia.

“What you cannot measure

you cannot manage,” Gosalia

said, “and what you cannot

manage, you cannot optimise.”

Fuchs identifies three levels of

sustainability. The first level is the

aforementioned “greenwashing;”

the second level is “sustainable

corporate control,” and the

highest level is “sustainable

enterprise.” Gosalia said that

Fuchs currently inhabits the

second level and is working on

moving to the third. A company

must be able to control and

improve itself internally before it

can aspire to bring sustainability

on social, ecological and

economic levels, he said.

“I think there is going to

be sustainable growth in the

Asia-Pacific [lubricants] market;

however, in the future on a much

lower level than we saw before,”

Gosalia concluded. Measured

in terms of volume, the growth

of the Asia-Pacific lubricants

industry may see a flatter slope

in the coming years, he said. But

its move toward higher quality

products means that it could be

contributing to the sustainability

of the other industries it serves.

Source: Fuchs Petrolub SE