The internal combustion engine: a brighter future?

Belgian-French engineer Jean Joseph Étienne Lenoir, is credited with creating the first commercially successful internal combustion engine (ICE) in around 1860. Nicolaus Otto, a German engineer, took it a step further by successfully developing the first modern ICE in 1876. With its foundations in Europe, the ICE has powered the modern world for almost 150 years through the movement of goods, personal and public transport. Though, until recently, the ICE vehicle appeared to be on its last legs in the European Union (EU).

New legislation requiring a 100% reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from all new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles looked like the death knell for fossil fuel-powered vehicles. Final approval of the law, designed to reduce the climate impacts of transportation, seemed like a formality. However, the legislation reached a stalemate at the eleventh hour when Germany’s Transport Ministry lodged a last-minute objection with the European Council on the EU-wide ban on the ICE, demanding an exemption for new cars running on climate-neutral e-fuels after 2035. An earlier vote by the European Parliament passed with a 340 pro ban, 279 against and 21 abstentions, underlining considerable opposition to an outright ban.

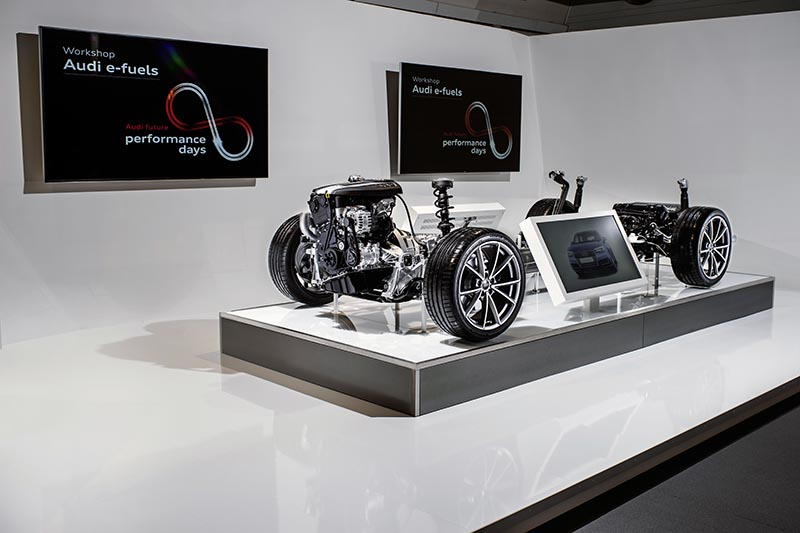

Germany is one of the global heavyweights when it comes to the manufacture of combustion engine vehicles and is home to leading brands Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, Audi, BMW and Porsche. The Western European country was concerned the ban could destroy the German auto manufacturing industry when a potential future for the ICE is accessible with the employment of climate-neutral fuels. Italy, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Czech, Austria and Slovenia seconded Germany´s motion.

A deal was brokered between the German Transport Ministry and the European Commission on March 25, 2023. Carmakers can continue to sell combustion engine vehicles after 2035, so long as they operate on fully climate-neutral fuels produced from renewable energy, which may include hydrogen.

The about-turn to permit e-fuels and to spare the ICE is a pivotal moment, not just for Europe and local automakers, but one that has global ramifications. 12 million motor vehicles are manufactured in the European Union every year with more than 5.7 million motor vehicles exported. The European Commission’s draft plan to allow e-fuel-powered ICEs after 2035 establishes a new type of vehicle category that can only operate on carbon-neutral fuels. Technology to prevent their operation with other types of fuels is likely to be mandated.

Synthetic or e-fuels can be produced by reacting CO2 and green hydrogen using 100% renewable electricity sources. The process begins with electrolysis, which separates water into hydrogen and oxygen, and the output can be refined into derivatives such as e-petrol, e-diesel, e-kerosene and e-methanol. Captured CO2 balances out emissions released when the fuel is combusted.

While the deal to allow modified combustion engines to continue to be used is a win for Germany, fuel manufacturers and automakers, Germany has a long way to go to decarbonise the entire manufacturing process and to achieve the climate-neutral fuel requirement in the legislation. Currently, 96% of hydrogen in Germany comes from natural gas and the region is heavily reliant on gas and coal-fired power plants for domestic power production.

Porsche is one of several OEMs that have advocated for the use of e-fuels. In a recent interview series, New Perspectives on Sustainability, Karl Dums, team lead at Porsche, discussed the future of e-fuels in the automotive industry, including the role of Porsche. Dums joined Porsche in 2008 and was involved in the electrification of the first Porsche vehicles, as well as leading the advance drive development and aggregate strategy, which included the launch of Porsche’s e-fuels project.

With the release of Porsche Strategy 2030, the German automaker confirmed it is focused on e-mobility in the development of future vehicles. Nevertheless, Dums believes we can only achieve ambitious climate goals by considering existing vehicles in the decarbonisation effort. There are an estimated 1.3 billion vehicles with combustion engines on the road. With an average lifespan of more than 12 years, ICE vehicles will be on our roads for decades to come. It is important to operate them as close to net carbon neutral as possible, says Dums. Porsche believes renewable energy and e-fuels will play a major role in solving this problem and as a complementary technology to e-mobility.

The potential of e-fuels as a “nearly carbon-neutral alternative” is huge, says Dums. Porsche is committed to employing synthetic fuels to reduce CO2 emissions.

E-fuels are not as technically efficient as batteries. In an article published by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) in mid-2020, the ICCT noted that 48% of renewable electricity can be lost in the conversion to liquid fuel with up to 70% of the fuel’s energy lost during combustion. Only 10% of electricity is lost in charging and 20% by the motor in electric vehicles. Even with anticipated advancements in e-fuel technology, batteries will remain the more efficient alternative, allowing longer travel than e-fuels using the same amount of renewable electricity.

Nonetheless, an ICE powered by e-fuels has many advantages that serve the needs of individual motorists—including a dense network of filling stations and the advantage of fast refuelling. Even though the distribution of renewable energy sources is unbalanced, e-fuels can be easily stored and shipped worldwide, whereas electricity is more suitable for nearby consumption.

The best sites for renewable energy generation have abundant natural resources. Dums highlighted the aptness of desert regions where the highest energy densities in the form of sun and wind are available, such as in southern Chile.

In 2020, Porsche announced it had entered into a collaboration with HIF Global, Siemens Energy, ExxonMobil and other international partners to build the ‘Haru Oni’ pilot plant in Punta Arenas, Chile. The company noted that the plant is the world’s first integrated commercial plant for producing climate-neutral fuel and it will leverage excellent wind conditions in southern Chile to produce e-fuels. Haru Oni officially opened in December 2022, which was marked by a ceremonial fuelling of a Porsche 911 by Porsche Executive Board members Barbara Frenkel and Michael Steiner.

According to a recent article published in Handelsblatt, Steiner, Porsche’s development director, calls the technology “the best solution I can think of” as a supplement to electromobility. Steiner can also “imagine” Porsche’s bestseller, the 911, as an e-fuel variant.

E-fuels currently are not yet produced at scale. Opponents have suggested the technology will still be in its infancy when Europe’s phase-out of ICE vehicles comes to pass. Analysis by Transport & Environment, a non-governmental organisation campaigning for cleaner transport—and a long-time critic of e-fuels—suggests that only five million out of the 287 million cars on the road can fully run on e-fuels in 2035.

Chilean operating company Highly Innovative Fuels (HIF) has started the industrial production of synthetic fuels at Haru Oni. During the pilot phase, Porsche expects 130,000 litres of e-fuel will be produced per year, which will be used in small-scale projects such as Porsche Mobil 1 Supercup and at Porsche Experience Centers. By mid-2025, the group will scale operations to 55 million litres per year, with capacity reaching 550 million litres approximately two years later. Dums also noted the strong potential for e-fuels in other applications beyond road transport including the aviation sector, shipping or even the chemical industry.

Recently, Norwegian, the largest Norwegian airline and one of Europe’s leading low-cost carriers, announced a landmark partnership with Norsk e-Fuel to build the world’s first full scale e-fuel plant in Mosjøen, Norway. The area has some of the lowest electricity prices in Europe as well as stable access to renewable energy from hydropower. This provides a considerate competitive advantage, as electricity constitutes a significant cost element in the production of e-fuels. Mosjøen has a port and rail infrastructure as well as a long-standing processing industry tradition. The goal is to start producing e-fuels in Mosjøen in Northern Norway as early as 2026. The partnership with Norsk e-Fuel is estimated to secure approximately 20% of Norwegian’s total demand for SAF until 2030.

Most of the aviation sector is more advanced in the defossilisation of jet fuels with airlines and their partners building capacity for millions of tons of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) from biomass.