The future of marine fuels: Ammonia or methanol?

There is no disputing the need to decarbonise the marine industry. From 2012 to 2018, total shipping industry emissions grew by nearly 10% and now account for approximately 3% of global emissions, according to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO). Unlike some other transportation sectors, alternatives to existing marine propulsion technology are not completely black and white. For short distances, point to point, or leisure boating, where infrastructure, power, or duration is not a critical element — there is a diversity of options emerging such as light batteries and hydrogen fuels. Once the application involves longer distances and global operability — there is a requirement for energy-dense fuels beyond battery and pure hydrogen solutions.

New marine fuels fall into two groups, zero-carbon fuels such as ammonia and hydrogen, and net-zero carbon-containing fuels, says Dorte Kubel, regulatory affairs manager at MAN Energy Solutions. MAN Energy Solutions is a multinational company that produces diesel engines and turbomachinery for marine applications. A subsidiary of German carmaker Volkswagen Group, MAN Energy Solutions already offers engines for a variety of marine applications such as gas, methanol, and existing hydrocarbons. The company is “looking into ammonia as a preferred option amongst zero-carbon fuels,” says Kubel.

Kubel provided insight into the opportunity for sustainable marine fuels during a recent CIMAC TECH Talk entitled Future Marine Fuels: A Look into the Crystal Ball. CIMAC, the International Council on Combustion Engines, is a non-profit association and a global forum for the large engine industry.

Methanol is a more well-known fuel, says Daniel Chatterjee, director, technology management & regulatory affairs at Rolls-Royce Power Systems AG. Methanol can burn in the engine or burn in a fuel cell. We have all options available to us — with some energy density. This becomes very interesting from our point of view, says Chatterjee. Though, he concedes diesel is difficult to compete with from an energy density perspective.

Best option for long-distance marine fuel

There are pros and cons to all marine fuels. So, what is the best option for long-distance marine transportation — ammonia or methanol? Chatterjee and Kubel provided observations on these two potentially ground-breaking marine fuels during the recent CIMAC TECH Talk.

The case for ammonia is relatively strong. Ammonia is a simple molecule, composed of three hydrogen atoms bonded to a single nitrogen atom. Importantly, ammonia emits no carbon dioxide when burned — forcing it into the spotlight when considering zero-carbon fuels. MAN Energy Solutions is developing an ammonia engine and supporting systems. We expect to have an ammonia engine developed by 2024 and are hopeful of having it on the water by 2025, says Kubel. Whether companies will purchase it is another question. The prerequisite is that someone is willing to invest in the new technology.

Despite its simple structure, ammonia is not an easy fuel. While it is carbon-friendly, Peter Müller-Baum, managing director, VDMA Engines & Systems, and moderator of the CIMAC event, highlighted the truth that ship operators commonly don’t want to use ammonia because it is toxic. Certainly, the toxicity of ammonia is a major concern. A spill of 3,000 litres of ammonia fertiliser in the U.S. state of Illinois in January 2020 hospitalised 80 people with chest pain, eye irritations, coughing, and severe headaches.

New set of skills and safety procedures for ammonia

Handling ammonia onboard vessels will require a completely new set of skills and safety procedures. We believe it is possible [to overcome safety concerns], but the issue requires cooperation along the entire supply chain, says Kubel. The industry needs to collaborate and find solutions — from ship designers and operators to port infrastructure. Safety issues need to be sorted and regulated by IMO, she says.

Ammonia is a widely traded commodity. Shipping and land-based industry has handled ammonia as bulk cargo for 100 years. This experience can be used as a basis for developing safety regulations and the necessary procedures to ensure ammonia is handled securely. MAN Energy Solution is undertaking all kinds of hazard analysis to build the necessary safety into the systems — including bunkering systems, says Kubel.

However, there is no experience using ammonia as a fuel. Combustion of ammonia in engines can also cause higher nitrous oxide (NOx) emissions, requiring additional techniques to control this greenhouse gas in a marine environment.

There is safety from a technical perspective, but it is equally important that people feel safe. The perception of ammonia will need to change for it to become accepted as a fuel. If we don’t have acceptance at a worldwide level, it becomes difficult to implement. If someone finds a good solution to handle safety, it will completely change the picture, says Chatterjee.

Putting aside safety concerns, a key benefit is that the ammonia market already exists with a worldwide distribution system, and it is a global commodity with transparent pricing. Currently, 80% of ammonia production is used exclusively in the fertiliser industry. A significant uptick in production would be required for ammonia use as a fuel — with some estimating current production would need to nearly double if 30% of shipping were to adopt the fuel.

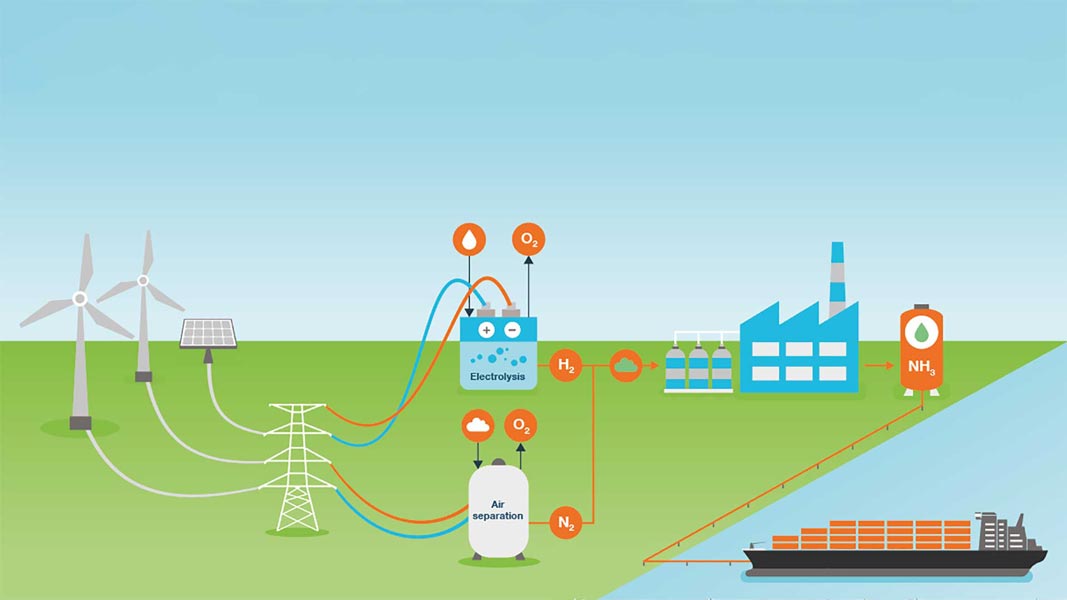

The bulk of the current supply is ‘grey’ ammonia — manufactured from hydrogen from natural gas, which generates carbon dioxide emissions. Only tiny amounts of ‘green’ ammonia are currently being produced. A trial plant in Fukushima Renewable Energy Institute in Japan, and a demonstration system at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire, England, are two notable factories – producing between 20-50 kg per day. Truly zero-carbon propulsion requires a shift to zero-carbon ammonia using ‘green’ hydrogen manufactured using renewable energy.

Ammonia gaining favor

One of the biggest challenges of alternative fuels is matching the energy density of current fossil-based fuels. Ammonia is not as compact as heavy fuel oil (HFO) but is acceptable and economically feasible for onboard storage. Ammonia has higher storage capability and involves less cooling than hydrogen — which requires more sophisticated cooling equipment.

Despite obvious drawbacks, ammonia appears to be gaining favour in the global shipping industry with a handful of projects underway — in addition to MAN Energy Solution’s efforts to produce the first ammonia fuelled oil tanker. Finland’s Wärtsilä plans to begin testing ammonia in a marine combustion engine in Stord, Norway, and the Norwegian energy company Equinor has signed an agreement to convert the Viking Energy supply vessel to carbon-free ammonia.

In a March 2021 media release, Maersk A/S, Fleet Management Limited, Keppel Offshore & Marine, Maersk Mc-Kinney Moller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping, Sumitomo Corporation, and Yara International AS announced a Memorandum of Understanding to jointly conduct a feasibility study on establishing a comprehensive supply chain for the provision of green ammonia ship-to-ship bunkering at the Port of Singapore, the largest bunkering port in the world.

Methanol is a clean-burning fuel

Methanol is a clean-burning fuel that produces fewer smog-causing emissions than conventional fuels. The attractive thing about methanol is you can start step by step, says Chatterjee. Methanol produced from natural gas offers a carbon dioxide benefit, despite being fossil fuel-based. From a technical perspective, methanol fits somewhere in between LNG and a diesel ship. You can use the same tank, you need some coating, but the tank shape is very flexible, he says.

Methanol is one of the top five chemical commodities shipped around the world and is already available for bunkering at over 88 of the world’s top 100 ports. Ships powered by methanol can be up and running with minor modifications to existing terminal infrastructure. The ability to roll into it slowly is not possible with ammonia — which makes methanol attractive as a starting point, suggests Chatterjee. Though, he concedes we need to produce it in a carbon dioxide neutral way in the end. Methanol produced from renewable sources is a strong candidate fuel for a sustainable future. However, methanol is a low flashpoint fuel, which requires some consideration, says Chatterjee.

Notwithstanding an increasing interest in methanol and ammonia, both panellists reiterated the importance of diesel moving forward. For the maritime industry to reduce real carbon emissions — we believe diesel as a drop-in fuel for high-speed engines is essential — otherwise, it will take a very long time, says Chatterjee. We believe e-diesel is one of the most important fuels. We have an existing fleet, and the renewable rate in the maritime industry is around 2% per year, he says. Ship operators might be prepared to pay a premium to convert e-methanol to e-diesel — due to a lower total cost of ownership. It may make more sense to pay a premium for fuel to keep existing installations operating, says Chatterjee.

.gif)